An introduction to functional data structures

13 November 2019Functional programming has become a major topic today on software engineering, mainly, due to the growing need to design asynchronous systems without the complexity of previous established thread-based model of imperative paradigm. There is a post in this blog that addresses this topic in a better way, explaining immutability. But even after reading that, you should keep in my mind some unanswered questions, like memory-related ones.

Usually, there are some engineers that believe that functional paradigm leads to a memory overload, due to its immutability and purity principles. Immutability(in terms of functional paradigm) is not only about copying data, but to keep referential transparency and the purity of functions. In order to accomplish that, there are some ways to determine data in terms of non-copying that and this post will illustrate an example of how that can be done.

We will implement a stack as a functional data structure. The example is quite simple, but perfect to understand how data can be handled without overload memory usage. Scala programming language(a functional programming language) will be used to implement this stack example.

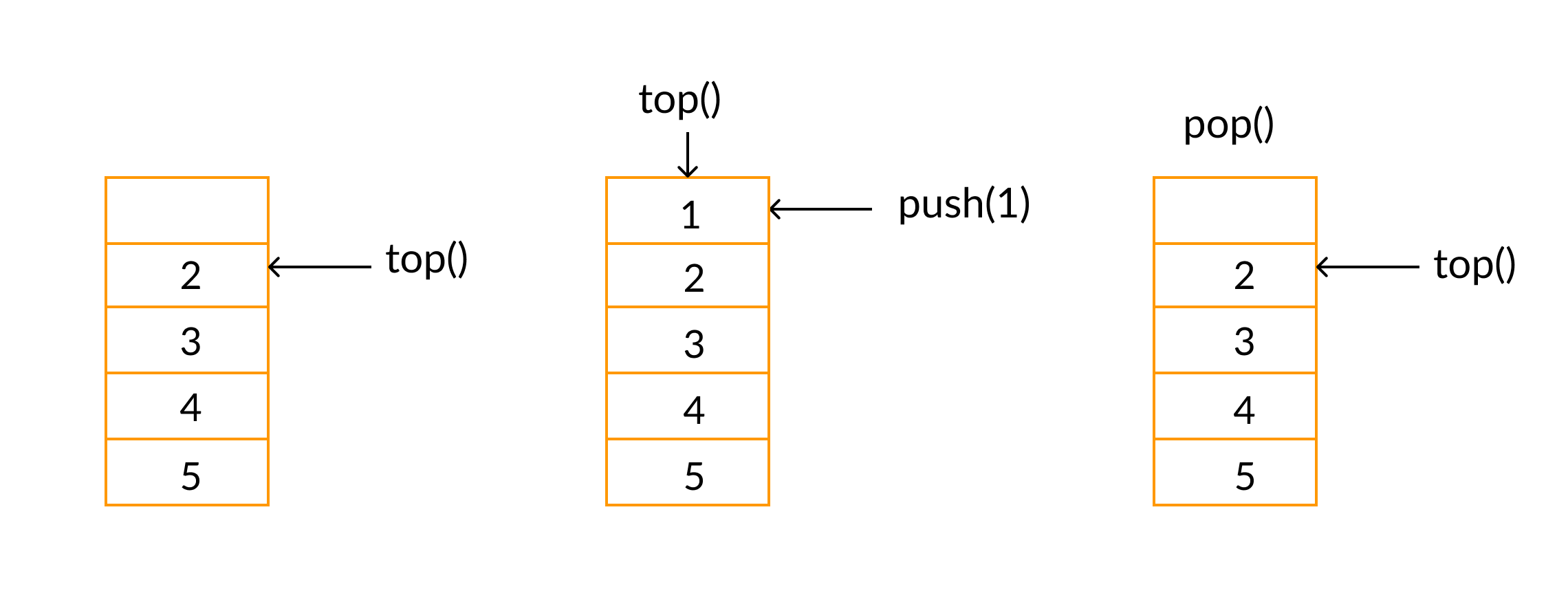

Firstly, it is nice to define what is a stack. A stack is a composite data-structure(collection) that can be called as LIFO(Last In First Out). A stack has the following operations:

push(element): adds an element to the stack.pop(): remove the last element added to stack.top(): get the last added element in the stack.

The image below can summarize it better:

Stack data structure for newbies

Stack data structure for newbies

Our first definition for it goes below:

trait Stack[+A] {

def push(a:A) : Stack[A]

def pop() : Stack[A]

def top() : Option[A]

}

Scalisms

Stack[+A]means that type parameterAcan be covariant. A type parameter is covariant when it admits that a subtype ofAcan be used in that generic representation.traitis something like a Javainterface.Option[A]is a null-safe wrapper for a nullable value. Something like JavaOptional.

With an abstract representation for the stack, it will defined two concrete components to accomplish stack implementation:

EmptyStack: This represents an empty stack.StackCons(head, tail): This represents a concrete stack with an element for the head and another stack for the tail.

Firstly, it will be defined what is an empty stack, as can be seen in the code below:

object EmptyStack extends Stack[Nothing] {

def push[E](element:E) : Stack[E] = StackCons(element, EmptyStack)

def pop() : Stack[A] = EmptyStack

def top() : Option[A] = None

}

Scalisms part 2

objectis a way to define a singleton object in scala. This singleton object can implement a trait and have an unique implementation for it.Nothingis a special type in scala that can be described as a subtype of all defined objects. When you use it in a generic specification, it means that it can be a subtype for everything.StackConswill be described with more details below, but it is exactly what we have said in its previous definition.Noneis a representation for a nullableOption.

With the EmptyStack done we finally can go forward to StackCons implementation:

case class StackCons[+A] (head: A, tail: Stack[A]) extends Stack[A] {

def push[E](element:E) : Stack[E] = StackCons(element, this)

def pop() : Stack[A] = tail

def top() : Option[A] = Some(head)

}

Scalisms part 3

case classis a representation available for immutable types. It is not necessary to use the keywordnewto create an instance of a case class, since its creation is basically the result ofapply()method. Read this for more details.Someis a representation for a non-nullableOption.

In this point, the implementation can be considered done. So that, let’s try to understand what was done:

- Observe that, in any part of already revealed code, it wasn’t touched any mutable data structure, and the functions of it just transform the input data that stack object receives, generating a new stack. That said, it can be concluded that this particular stack implementation is a pure functional implementation.

- A typical stack implementation over mutable state has arround 40 lines of code and would need more if something thread-safe is desired. Pure functional one has less than 20 lines of code and doesn’t need to care about concurrency since it is not a problem in a pure functional environment.

- Regarding memory, it can be recognized that any copy operation is performed over data. Instead of it, already defined data is used to compose the stack as you can verify in

push(element)implementation atStackConscase class.

Our stack implementation can be improved thought a factory singleton object, that would be useful to instantiate our stacks.

object Stack {

def apply[A](arguments:A*) : Stack[A] =

if(arguments.isEmpty) EmptyStack

else StackCons(arguments.head, apply(arguments.tail: _*))

}

Scalisms part 4

A*means for variable arguments.apply(args:A*)function can be be executed without being properly called. In that case,Stack.apply(arguments*)andStack(arguments*)means the same thing.: _*is a casting from aSeqobject(arguments.tail) into variable arguments.

With Stack object, this implementation can be tested and verified:

scala> import chapters.two.Stack

import chapters.two.Stack

scala> val stack = Stack(1,2,3)

stack: chapters.two.Stack[Int] = StackCons(1,StackCons(2,StackCons(3,EmptyStack)))

scala> stack.push(4)

res0: chapters.two.Stack[Int] = StackCons(4,StackCons(1,StackCons(2,StackCons(3,EmptyStack))))

scala> // please observe here that REPL create another variable for the transformed stack(`res0`)

scala> stack

stack: chapters.two.Stack[Int] = StackCons(1,StackCons(2,StackCons(3,EmptyStack)))

scala> // here you can verify that the stack remains untouched, immutable.

scala> stack.pop

res2: chapters.two.Stack[Int] = StackCons(2,StackCons(3,EmptyStack))

scala> stack

res3: chapters.two.Stack[Int] = StackCons(1,StackCons(2,StackCons(3,EmptyStack)))

scala> // same for pop() operation.

scala> stack.top

res5: Option[Int] = Some(1)

scala> stack.push(4).push(5).pop

res6: chapters.two.Stack[Int] = StackCons(4,StackCons(1,StackCons(2,StackCons(3,EmptyStack))))

scala> stack.push(4).peek

res8: Option[Int] = Some(4)

It looks nice for now, but you may be thinking about how that can be used in a real-world application. Unfortunately, this will be a topic for the next post. For now, it is just necessary to make you rethink about the general idea of “copying” everything when you think about functional programming.

See you in the next posts, thanks for the reading.